In 2019, reports of racism increased for the seventh consecutive year within English Football. Kick It Out, an organisation promoting greater equality and diversity, stated that the amount of racism being reported has more than doubled in the last five years. Such findings are indicative of an alarming global trend of increased racism across all sports. This trend was more apparent than ever in 2019.

The level of racism plaguing Italian Football was evidenced by the abuse of Moise Kean in April and further compounded by the headlines of Corriere dello Sport towards the end of the year. France also saw record-levels of racism directed towards players of their Ligue 1. The abuse of Amiens’ defender Prince Gouamo preceded the cessation of their match against Dijon for several minutes on the 12th of April.

International football highlighted the extent of the issue. As early as March, England’s Danny Rose was subject to racist abuse from Montonegrins in a European Championship Qualifier. However, the blatant racism demonstrated in Sofia – where England travelled to play Bulgaria – elicited national outrage and disgrace.

How is football ‘tackling’ racism?

Internationally:

The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) were the governing body responsible with establishing an adequate punishment for the Bulgarian national team and it’s fans. The UEFA protocol for racism is to issue an announcement inside the stadium which orders the racism to cease. Unsurprisingly, this has a very limited effect – nazi salutes and monkey chants continued from a group of Bulgaria fans.

In the aftermath, rather than condemn the racism, Bulgaria’s manager, Krasimir Balakov, claimed he ‘didn’t hear’ the abuse and failed to offer an apology on behalf of the Bulgarian national team. His resignation came four days after the match along with that of Borislav Mihaylov, President of the Bulgarian Football Union, who had also questioned the extent of racism on show.

UEFA were widely encouraged to make an example of Bulgaria by removing them from the European Championship altogether. However, the resignations of both the manager and the president were seemingly rewarded with relative leniency; Bulgaria received a €75,000 fine and a stadium-ban for two games.

A number of organisations openly criticised UEFA’s punishment with Kick It Out stating that they had “missed an opportunity” to take an uncompromising stance against racism in European football. Football Against Racism in Europe (FARE) echoed this response, stating their disappointment that Bulgaria had not been expelled from the Euro 2020 qualification process.

Domestically:

In the wake of heightened instances of racial abuse reported throughout English football in 2019, the Football Association (F.A.) insists they have made “huge strides”. They cite their ‘In Pursuit of Progress’ initiative (introduced at the start of 2018) as well as their collaboration with Kick It Out – funding the appointment of two additional ‘grassroots officers’.

Conversely, Kick It Out seem to bring into question the nature of this collaboration. They state that the F.A. are yet to inform them as to the outcomes of nearly 100 discrimination cases reported in grassroots football. Thus, the ‘collaboration’ the F.A. professes to have established with Kick It Out is seemingly an ineffective and purely superficial one.

In the Summer of 2019 Kick It Out CEO, Roisin Wood, suggested increased reports of racial abuse within English football could be linked to the political climate, namely Brexit. Here, Wood points to the differing focus and rationale behind the racism in recent years, referencing increased reports of “go back to where you came from”. This politicised racism forces us to question the role and responsibility of the media in dealing with racism.

The Media: Racism’s friend or foe?

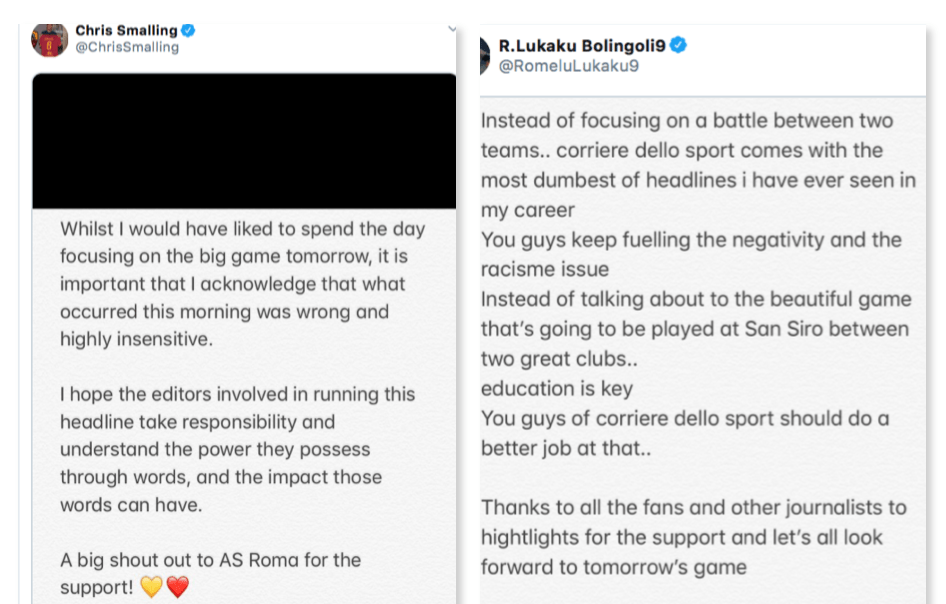

This headline was given editorial approval and circulated on the 5th of December 2019 after a year of unprecedented racial abuse in Italian football. The newspaper was widely condemned by football clubs and players, primarily Chris Smalling and Romelu Lukaku alongside their respective teams AS Roma and Inter Milan. FARE referenced the headline in a tweet with the caption, “The media fuels racism everyday”.

Corriere dello Sport responded aggressively the following day with the headline: “RAZZISTI A CHI?”. They posed the question ‘who are you calling racist?’, after a precursive statement in which they portrayed themselves as defenders of ‘liberty and equality’. Such a response was not surprising. In April 2019, Moise Kean (then of Juventus) was urged to shoulder half of the blame by team-mate Leonardo Bonucci after receiving racial abuse from a group of Cagliari supporters.

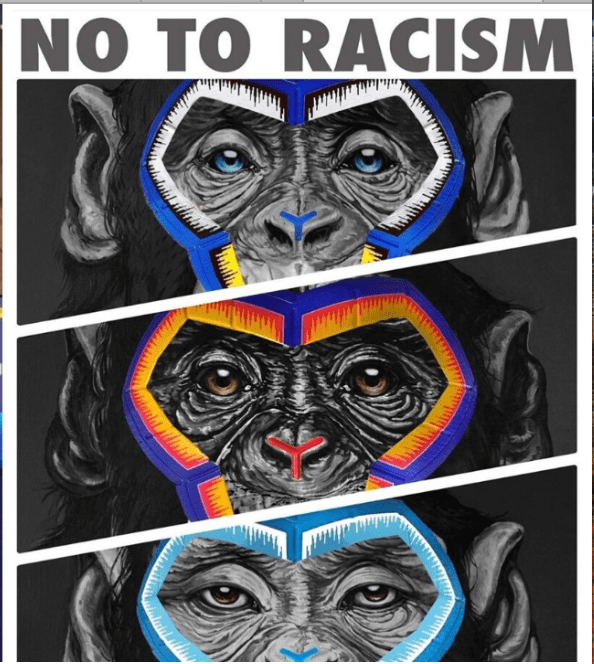

This evident ignorance within Italian football towards the issue of racism was only underlined by the Serie A’s (Italian first division) ensuing attempt to combat racism. Their ‘anti-racism’ artwork (pictured below) was branded ‘counter-productive’ and seen to be exacerbating rather than alleviating the problem. Artist, Simone Fugazzotto insisted that the intention of the artwork was to demonstrate that “we’re all apes”, yet his and indeed the Serie A’s inability to foresee how this may be perceived was, at best, extremely naive.

Power to the players?

Early in 2019, the Professional Footballer’s Association (PFA) encouraged players to boycott social media for 24 hours in response to racial incidents as part of the #Enough campaign. Not only was this campaign not ‘enough’, it demonstrated that the PFA were out of touch with modernity. Social media is a tool. Football players should be praised for utilising their platforms to combat racism, to share their own experiences with racial abuse and to appeal to their millions of followers to stand with them against racism in football and in society.

Manchester City’s Raheem Sterling effectively exploited his social media presence to raise awareness of and support against racism throughout 2019. Others followed suit with both Romelu Lukaku and Chris Smalling taking to Twitter in response to the ‘Black Friday’ headline of Corriere dello Sport. They outline that while social media is a breeding-ground for racism it is also increasingly the front-line in the fight against it.

In addition to social media, football players can also make use of their own free will. Leaving the field of play in response to racial abuse is often discouraged and portrayed as a triumph of racism. In November 2019, the infamous Mario Balotelli was prepared to walk-off the pitch after being racially abused while playing for Brescia in the Italian Serie A. However, both his team-mates and match officials persuaded him to stay on the pitch and play-on.

Ironically, Mario would go on to score in the 85th minute of the game yet it wasn’t enough to overturn his team’s two-goal deficit. The game ended 2-1.

The result that day is symbolic in many ways of the current fight against racism. Minor and temporary victories like Mario’s goal should not obscure the broader picture of a losing battle. After the game, Mario took to Instagram to condemn the racism and thank his team-mates for their ‘solidarity’. Had his team-mates demonstrated true solidarity that day, the entire Brescia team would have left the pitch – the match abandoned, the show over.

Any player who, having become the victim of racism, decides to leave the pitch and have no further involvement in the match should have their decision collectively embraced rather than discouraged. Football’s biggest allies in the stand against racism are football fans. They need to be incentivised to counter racism whenever they witness it.

The most effective way to achieve this is by depriving them of the football they pay and travel to watch on account of the racism which they frequently turn a blind-eye to. While this approach may seem hardline, it is the only way to ensure that the perpetrators of racism are held accountable. Held accountable by members of their own community within football. Perhaps then an adequate resistance to racism will be established.